The Origins of Urban Food Movements: A Case Study of Portland and Detroit

The Origins of Urban Food Movements: A Case Study of Portland vs. Detroit

UW-Madison Task Force Members:Sarah Walker, Department of Community and Environmental Sociology

Saida Chacon Cedillo, Department of Nelson Institute

Will Lundeen, Department of Pediatrics

Abstract | Introduction | Methods | Scenario | Historical Background | Case Study 1: Portland | Case Study 2: Detroit | Discussion of Results | Limitations | Conclusions | Citations | Acknowledgements |

The material on Portland's history, both economic and racial, is compelling and well covered. There are also pieces that cover the connection between the two, which is crucial to understanding how race and economics are intertwined for the city and metro area in general. However, we believe our research and discussion will take this historical lens one step further and connect it to the conversation surrounding race, class and the local food movement in Portland. While hailed as a progressive move towards local food and urban food availability, Portland's movement is criticized for gentrifying effects and racial exclusion. Connecting these criticisms with the historical framework of the city overall, in terms of economics and race, will allow us to discuss the roots of this criticism and how the city can and should react.

Detroit's history as the Motor City of America is colorful and dramatic, starting with a rapid and exciting boom in the 1920's and culminating in a graphic story of race riots, white depopulation, and a crumbling manufacturing economy in the 1960's and 70's. The literature on Detroit covers the rise and fall comprehensively, however - similar to the research in Portland - it only vaguely connects this rich background with the characteristics of it's modern food justice movement. The urban food movement in Detroit has its roots in race and class, and we believe our historical research will be able to connect those roots with Detroit's history.

Urban food movements have gained a lot of publicity and political support in the last few decades through their successful response to different cities’ unique food issues. However, there have not been in-depth discussions comparing food movements alongside their cities’ historical backgrounds. We believe that this deeper analysis will be helpful in understanding the roots of differences between movements, as well as how they can and should progress in the future. For our comparison, we chose Detroit, Michigan and Portland, Oregon. These two cities have comparable population sizes, which we believe is a crucial foundation for a comparison. In order to fully understand these two cities’ famous food movements, we first turned to the racial and economic histories of the two cities, beginning with the statehood of Oregon and Michigan and following the ebb and flow of their demographics and economies through the 20th century. This information allows us to fully understand and analyze how and why the differences we observe in their food movements arose the way they did. As you will see in the coming section, our in-depth research and analysis of journal articles, podcasts, news articles, legislation, primary interviews, and demographic data allow us to draw conclusions to our questions about the differences between the two movements.

We explored our research questions, thereby putting our hypothesis “to the test,” through comprehensive research of academic journals, newspaper articles, demographic statistics, and a primary interview. We compiled indepth research and analysis of existing works on the history of both Portland and Detroit and modern day demographics of the two cities, with the goal of comparing the racial and economic stories of the two cities. We also analyzed extensive work on the urban food movements in both Portland and Detroit, and we plan to include a primary interview with Monica White in our final paper and presentation. This interview will also affect our discussion and conclusion sections, and adjustments will be made after the interview is completed.

As the urban agriculture movement sweeps the nation, it comes as no surprise that we were hired to advise the growing city of Denver on how to foster their own movement. As experts in the field, the three of us were hired by the city of Denver to study two other successful urban food movements in the United States: that of Portland, Oregon and Detroit, Michigan. We believe that our historical, spatial, temporal, and racial analysis of these two movements will allow us to speak on the differentiated strengths, weaknesses, and futures of food movements in American cities. Below is our analysis and conclusion from our study of Oregon and Detroit; we hope it is thorough, instructive, and compelling.

Often hailed as one of the most progressive cities in America, Portland has a reputation for liberal politics and a ‘hippie’ population. However, this surface level image fails to recognize the overt racism deeply entrenched in both Portland and Oregon's’ histories. Semuels notes that racism is even embedded in Oregon’s 1857 state constitution, where it became and remained the only US state to explicitly forbid African Americans from living within its’ borders in history. Detroit, and Michigan more generally, has a very different history of race and law. Following the Civil War, in 1838 ‘black codes’ were silently removed from the state legislation for lack of support and enforcement. Overall, African Americans in Michigan were protected by extremely progressive legislation for the time compared to their counterparts in Oregon.

At the turn of the 20th century, Portland and Detroit’s economies were taking shape. Oregon’s industry was heavily based in natural resource extraction and transportation, including timber, salmon, and mining. These products concentrated themselves in Portland as the first cross country railroads were built (“Oregon History..” 2018). Meanwhile, Detroit’s reputation as the motor city of the United States was starting to build. Though the city was in competition with Cleveland at the turn of the century, the federal support for Standard Oil, and therefore a gas powered car over an electric car, solidified Detroit as the forerunner. Soon after, Ford and Dodge solidified the infrastructure for the Motor City and there seemed to be no going back (Kurczewski, 2016).

Post WWII, increasing domestic consumption and high-level government contracts bolstered both Portland and Detroit’s economy. Portland received a massive contract for the Kaiser Shipbuilding Corporation to build two huge shipyards and expand the existing shipping infrastructure of the city in 1942 (Fryer, 2004). With this economic boost came an immigration of low-income workers looking to fill the hundreds of open manufacturing jobs. White Portland residents worried that this would affect their city negatively, as the city had never had more than 2,500 African Americans and discrimination was embedded in their history (Fryer, 2004). When Kaiser lobbied to build new housing for these migratory workers, anti-housing protests took over Portland.

In contrast, Detroit’s newfound reputation as the Motor City of America catapulted its manufacturing industry into the post WWII atmosphere. These manufacturing jobs represented an exceptional opportunity for uneducated workers, especially WWII veterans, and white workers dominated the industry similarly to Portland, partly because of private enterprise discrimination (Kurczewski, 2016). Detroit’s population peaked in 1950 at 1.85m people having grown from less than 300,000 in 1900, and close to 85% of Detroiters were white (Galster, 2017).

Though both cities established booming economies in the first half of the century, the second half of the century tells a story of growing differences. While Portland remained a strong natural resource and transport center, moving factories shook Detroit. As Portland’s housing remained extremely segregated, Detroit’s demographics completely flipped and white flight decimated the city’s tax base.

In the early part of the century, the Portland Realty Board declared it unethical to sell property in a white community to non-whites as it devalued property in the area. This combined with Portland residents continuously rejecting plans to build affordable housing, lead to the degradation and spatial concentration of housing available to African Americans over time. Later, these segregated areas were targeted by urban renewal projects; though advertised as an urban renewal project, many residents renamed it a ‘negro removal’ project for the city’s failure to help displaced communities relocate (Mcelderry, 2001).

Detroit also experienced housing segregation, though it arose for very different reasons and across a wider space. Detroit’s economic foundation began crumbling in the 1950s for three main reasons, as outlined by George Galster in his book Why Detroit Matters. The first causal factor was the movement of manufacturing plants out of the city to the suburbs. This massive shift meant that many low income African American manufacturing workers no longer had spatial access to reliable jobs. Second, white Detroiters followed the jobs to the suburbs; African American residents don’t have that same option because of housing discrimination in suburban real estate. Lastly, this “white flight” lead to a gutted city tax base. As a result, the inner city had few job opportunities, limited mobility, lower real estate value, and an extremely restricted tax base for public services.

These anxieties culminated in the horrific 1967 Twelfth Street Race Riots, pitting inner city African Americans against the police. Over five days of rioting, 43 people were killed, 467 were injured, more than were 7,600 arrested, with 2,000 buildings destroyed (Galster, 2017).

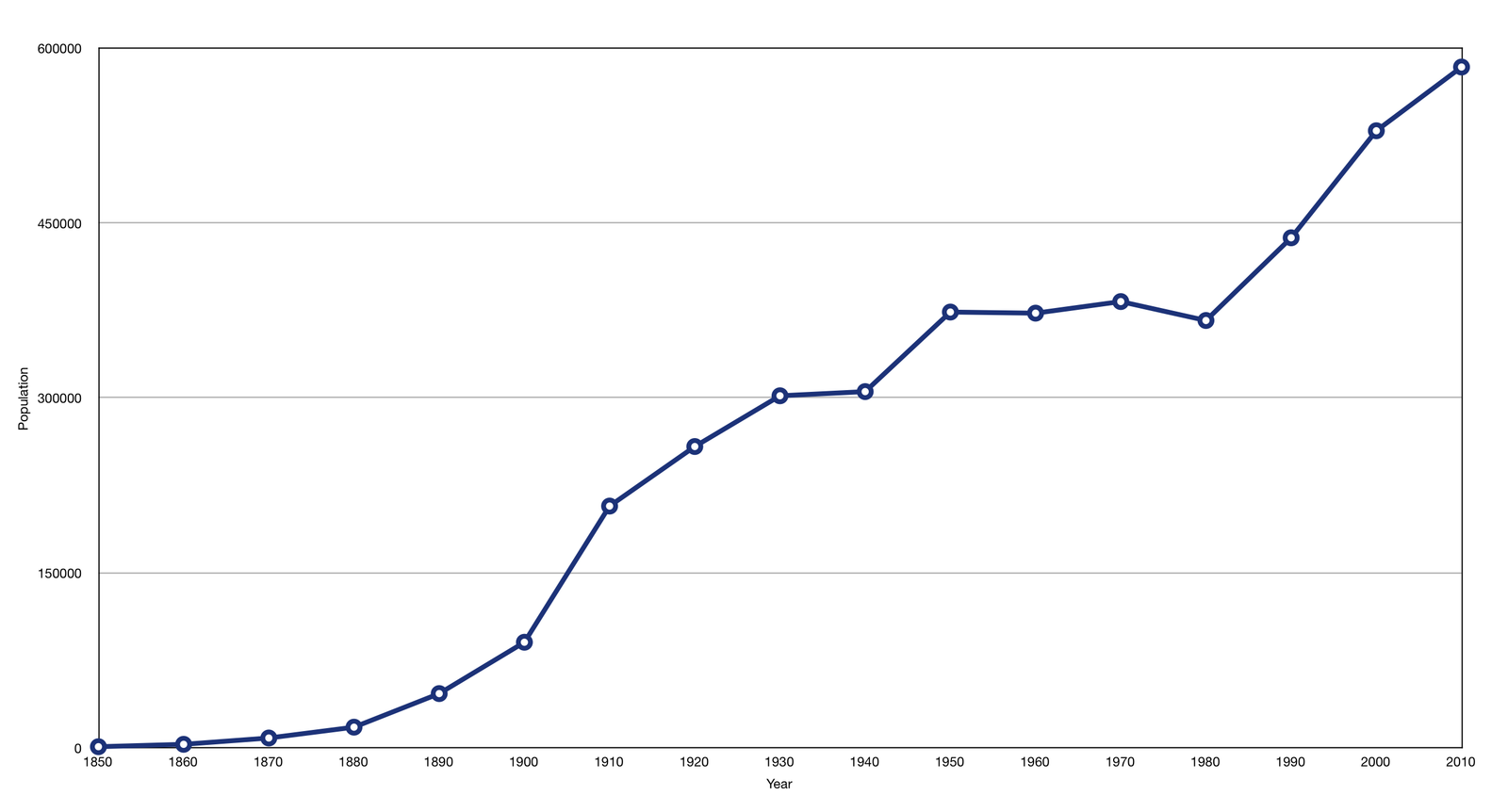

Graph of Portlands' population in the 20th century (Wikimedia Commons).

Graph of Detroits' population in the 20th century (Eley, 2011).

The Portland and Detroit areas are dramatically different today. The two cities have similar populations - 632,309 and 677,000 respectively - and very few other similarities. Portland is about 76% white while Detroit is about 83% African American, showing the dramatic effects of the late 20th century white flight in Detroit. Portland has an unemployment rate of 5.9% while Detroit has 13.2% unemployment, once again showing the effects of the economic vacancy of Detroit after the major manufacturing companies moved to the suburbs. Portland has a median home value of $295,000, almost seven times Detroit’s median value of $42,300. Lastly, the massive depopulation of Detroit has left the city with a 30% vacancy rate compared to Portland’s 5.8% (World Population Review, 2018).

Dot map of Portlands' 2010 population by race (University of Virginia, 2010).

Dot map of Detroits' 2010 population by race (University of Virginia, 2010).

The Portland Food Policy Council: Addressing the Local Population

Portland, in the late 20th century, became the hub for metropolitan growth in the Pacific Northwest. As Wendy Mendes notes, as early as the 1970’s, “Portland [was] shaped by the Oregon state land use planning system that requires each city of metropolitan area to set an urban growth boundary (UGB)” (Mendes et al. 2008). This instance was the first time in Portland’s history that city planning was used in order to defend against the inevitable boom of “sagebrush subdivisions, coastal condo mania, and the ravenous rampage of suburbia” (McCall, 1973), a process that, over three decades, prevented the growth of urban portland from 88 to 279 square miles of urban development (Mendes et al. 2008). Over these decades, the diversity and housing markets have changed substantially, marked most prominently by a dominant white population; nonetheless this attitude towards sustainability of urban land has led the local community to adopt a pre-existing commitment to methods of sustainable development with (lackluster) emphasis on the promotion of cultural food policy. More recently, this led to the establishment of the Portland Food Policy Council in 2002, stating, ““urban land use policies and rules negatively [affect] local food populations” (City of Portland 2007). A recent survey conducted of 17,000 Portlander’s reflected this concept, as they, by name, included sustainability as a “core concept” of the city’s overall goals (Mendes et al. 2008).

The “Diggable City” Project, promptly formed in 2004 by Portland Commissioner Dan Saltzman, was originally a project meant to inventory urban land with potential for use for community gardens. The initial kick-start of the program provided city with extensive urban mapping and planning methodology. In an effort to expand the project, the 8 members of the initial Diggable City project included all city-owned lands within their first analysis in an effort to show the wide and extensive variety of urban land usage (Balmer et al., 2005).

Figure 5 In place of lacking state and local government financial support, The initial kick-start of the program provided city with extensive urban mapping and planning methodology. In an effort to expand the project, the 8 members of the initial Diggable City project included all city-owned lands within their first analysis in an effort to show the wide and extensive variety of urban land usage (Balmer et al., 2005).

The end of the project concluded with five recommendations, summarized within the original publication of the Diggable City Team (Balmer et al., 2005).

- Develop an inventory management plan

- Expand the inventory and develop evaluation criteria

- Form an Urban Agriculture Commission

- Adopt a formal policy on UA

- Conduct a comprehensive review of policy and zoning

The city of Portland unanimously accepted the results of these terms in 2008, a staple in local commitment to the prospects of sustainability. Since the establishment of these goals, the Portland Food Policy Council has released yearly reports and pamphlets in an effort to educate the public, on surface levels, of ways in which UA can be adopted. The local government in Portland makes frequent use of both university and non-profit sources to do so, such as the Post Carbon Initiative. The need to do so stems from the initial underfunding of the local food movement by the state government and the effort by non-profits to aid struggling local restaurants, consumers and producers involved in the Portland local food movement. The Post Carbon Initiative, a non-profit organization based in Portland, working with the University of Southern California, is a good example of this process. Their pamphlet, The Planner’s Guide to the Urban Food System, attempts to spread the knowledge of food systems in general, providing both city planners and residents of Portland with the resources for creating a system of UA that is both sustainable and secure. This non-profit is also Portland’s leading effort in sustainability networking, as they provide, both in their pamphlet and online, sources for “opportunity and immediate action” on a local level. The organization encourages the use of Portland’s local food movement as means for solving these issues; the common theme being sustainable UA as the solution for city wide problems through various efforts. These include the urging of the Oregon state government to require public institutions to purchase a set percentage of local food and fostering a network between local producers, middlemen and consumers. Wendy Mendes terms the phrase “networked movement” as a way to describe the community involvement of Portland, a process that “promot[es] more inclusive and participatory local decision making, and encourag[es] citizen engagement and buy in”.

In Portland, the trend in organizing city sections and local economy for UA has been specifically based on the land inventories provided by the original Diggable City Project team. The overwhelming success of Portland in creating an environment of sustainability through the Diggable City Team has to do specifically with the creative ways in which the local government began to interact with the community, in place of their inability to financially fund these projects. Wendy Mendes tells us, “Portland also used nontraditional outreach techniques that highlighted storytelling and relating personal experiences. One notable example was a 22-minute documentary created by the students that won an award in a local film festival, and has since been distributed to many local and national interest groups as an educational tool” (Mendes et al. 2008). This extended local community involvement has more recently provided local citizens with platforms to speak their own opinions on matters of community importance. Of note is the Racist Sandwich podcast, a platform produced by a team of people of color. Their mission, according to their website, is to, “serve up a perspective that you don’t hear often: that both food and the ways we consume, create, and interpret it can be political” (RacistSandwich.com).

Detroit went through a great economic depression for various years even before the economic decline that the whole country suffered (Kaza, 2006). Unfortunately, numerous socio-economic negative impacts were exacerbated in Detroit. According to the 2009 US Census Bureau, American Community Survey household incomes fell by 31% since 2000 thus becoming the poorest city in America, with 28.3% of families living below the poverty level. As a consequence, the Detroit metro became the most racially segregated in the country (Pothukuchi, 2015). As expected the food sector became more suburban, global and concentrated (Hendrickson and Heffernan 2007). Grocery chains developed large-footprint formats and investment in small stores was almost eliminated affecting inner-city poor residents (Pothukuchi, 2015). The problem culminated when the last major grocery store chain closed (Smith and Hurst, 2007) and almost 50% of the residents flight from the city leaving a lot of vacant lots behind. Now on days, Detroit is considered as a 'food desert' (Zenk et al., 2005) (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Map of Detroit showing neighborhood boundaries and USDA-designated food desert census tracts (Colasanti et al., 2012).

To mitigate these consequences redevelopment efforts were shaped primarily by the need to attract investment to the city and create jobs however these were considered too little, too late, and did little to revitalize neighborhoods (Pothukuchi, 2015). Thankfully a surge of interest in the topic of urban agriculture and its potential impact on aging industrial cities found a particular focus in the Motor City. According to its proponents, urban agriculture would be the right path to address several of Detroit’s most pressing issues at once: first, by putting land to use, converting vacancy from a deficit to an asset; second, providing access to fresh and healthy food in areas where grocery stores are in short supply; third, employing people to work on the land, much-needed jobs for low-skilled workers left behind by deindustrialization would be provided producing economic gains for the city, not only through profits and wages but also through the localized production of value-added, food-based commodities; and finally, it will promote social cohesion, individual responsibility, social justice and other less tangible but no less significant outcomes (Mogk et al., 2008;Colasanti et al., 2012).

Indeed, the rise of urban agriculture coincides with economic depressions in modern history, when state and local governments promoted community gardens to counteract poverty and its attendant social unrest (Schukoske, 2000). But in Detroit this recent manifestation of urban agriculture is unique; it is a movement driven by social justice as well as necessity, incorporating an ethic of environmental sustainability and all the challenges faced by the community mentioned previously (Mogk et al., 2008). The city exhibits a prime example of urban agriculture as a grassroots movement that shifts how the community thinks about food, where it comes from, and who controls it. Most importantly, Detroit's urban agriculture movement has stimulated the idea of access to healthy affordable food as a human right. The first steps that this movement took were when the local black nationalist leaders insisted on the development of home-grown institutions organized around cooperative rather than capitalist principles (Pothukuchi, 2005).. In 1975, when the city was already surrounded by anguish and almost 43.7% of the population was African American because of the urban crisis (McDonald, 2014), the Farm-A-Lot Program was initiated by Mayor Young, giving gardeners assistance to grow crops on the abandoned plots (Mogk et al., 2008). With reference to the grassroots initiatives, a group of seniors, who named themselves as the Gardening Angels, set up community gardens in the 1980’s becoming part of the first projects (Boggs and Kurashige, 2012). Immediately as a fortune consequence the first cooperative businesses of and for the black community, including the Black Star Market, a grocery cooperative, were also developed. This cooperative was led by Pastor Albert Cleage, founder of the Central United Church of Christ, later renamed the Shrines of the Black Madonna of the Pan-African Orthodox Christian Church. This group offered both a vision and a program for a self-reliant community food system that continues to inspire grassroots efforts today (Pothukuchi, 2015).

Detroit is estimated to host between 350 (Duda, 2012) and 1,600 community, school and institutional gardens or farms, producing 165 tons of harvests per year on 0.4% of city-owned vacant land (Gallagher, 2010). The size of the operations ranges from backyard plots to two acres, while the largest of the six small farms operate on seven acres (Figure, 7) (CPC, 2013). Mainly cultivating vegetables, fruits, and herbs, the farms produce food for sale through a dozen farmers’ markets, direct sales to restaurants, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) networks, and soup kitchens as shown in figure 7.

Figure 7: Map of Detroit showing urban farms, community and school gardens, farmers’ markets and produce markets, dairies and community supported agriculture (Colasanti et al., 2012)

Currently, urban agriculture keeps supporting racial freedom, through grassroots programs that have been very successful such as the Detroit Summer program or the urban farm of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network (DBCFSN) with one of his largest farms known as D-Town. This programs through the production of fresh and healthy food, workshops, cooking demonstrations and training sessions not only empower the black community as a whole but especially black women who are particularly negatively affected by inadequate access to healthy food (White, 2011). Unfortunately, because most of these projects start from inside the community but don't get to higher political or government levels other programs like Hortaliza have to be finished. In fact, Hortaliza was thriving, a lot of kids from the neighborhood were involved and there was an overall improvement in the community regarding their diets and the development of relationships between the members of the community. But things like secure land tenure, not having building permits, appropriate waste management, amongst others, led to the termination of the project (Pothukuchi, 2005).

Why Did These Movements Start?

In Portland, the movement towards local sustainability began due to choice of the community. Legislators recognized early on that the metropolitan area of Portland was growing substantially around the 1970’s and made an active effort to publicize the need for methods of urban control. In this vein, most of their sustainability movements have arisen from popular local culture. In many cases, political “hero” figures, such as Dan Saltzman (the man who drafted the original outline for the Diggable City Project) or activist movements/non-profits, such as the Post Carbon Initiative, have used their positions of power to promote the spread of urban sustainability. The use of popular culture as means for promoting local sustainability helps to explain the rapid success and expansion of food programs within Portland - both the residents and their culture reflected a desire for a more environmentally friendly future. This push for sustainability was possible because of the historically strong relationship between the predominantly white urban population and the representatively white political body serving it. On the other hand, the political and economic situation in Detroit pushed the community to find a way of providing food access for themselves. Urban agriculture seemed to be the answer to that necessity by generating empowerment and giving the community the ability to make decisions. Since then, the grass root movement became strong and shifted the way the community thinks about food, where it comes from and who controls it. As a consequence, the urban food movement stimulated the idea that food should be a human right. This becomes the foundation for the development of the community and the search for different ways of securing their food. The fight for urban food justice and access was necessitated as a result of Detroit's declining economy, starting in the 1950s and culminating in bankruptcy. Community members were not being served by their budget-less political body and had to take action themselves in order to answer the questions of food access in a declining city.

The strength of Portland’s local emphasis on sustainability arises from the people themselves. At first, this concept was a disadvantage for the residents of Portland - future security rested on their shoulders, as the local and state government had not set aside funds for projects (like Diggable City) or to staff policy makers (as with the Portland Food Policy Council). This fueled the integration of grassroots movements, activist groups, non-profits and concerned citizens into a strong and homogenized community. However, as years passed and Portland became solidified as a “white” city, the concept homogenous population began to gentrify the relatively small community of colored people within Portland metropolitan limits. Many people of color in Portland feel misrepresented and underappreciated as local chefs, farmers and entrepreneurs, reflected in the Racist Sandwich podcast - a Portland-based production that interviews local chefs and observes culture within city limits.

The strength in the case of the community network in Detroit by being in a very difficult situation to have access to local fresh products the grassroots movement became very strong as each of the members shared the same needs and disadvantages. In addition to these just after the vacancy lots became an evident opportunity of accessible land, urban agriculture turned into the golden opportunity to overcome their unfortunate situation. All of these building up a strong local food movement created and nurtured inside the community for the community. However, the major weakness showing is that there is a lack of government involvement therefore a lot of these efforts are dissipated and a long-term positive impact in the community has not been sustainable throughout the time.

How Each City's Movements Can Improve

Moving forward, the marginalized population of Portland has begun to use the historically local platform of Portland to both express their frustration with the gentrification of their cultures, a sign that the people of Portland are making steps towards political and economic equality. This platform, when utilized to its fullest extent could provide a powerful and massive tool to speak out against the overwhelming and historical racism of Portland’s metropolitan area. There is growing support for this trend, as the most prominent outlet for colored people (in regard to local culture) is the Racist Sandwich podcast, which has achieved national success within less than two years. In the past, these communities have been extremely misrepresented, most viciously by the Oregon state government and housing restrictions, but now have a light at the end of their tunnel - Portland’s power lies within the spoken word, a unique situation that could prove to be very beneficial in the representation of the misrepresented residents.It is true that grassroots movements become strong by being nurtured and followed up by the community. Nevertheless, because of the economic and political situation that at the moment is still impacting the people inside the community, resources and efforts must be brought from the outside. This makes reference to the political support that should go hand in hand with the community efforts to establish a system that should be continually fed to generate positive and steady results. Spread the word, get recognition and increased representation and therefore funding

For Detroit is true that grassroots movements become strong by being nurtured and followed up by the community. Nevertheless, because of the economic and political situation that at the moment is still impacting the people inside the community, resources and efforts must be brought from the outside. This makes reference to the political support that should go hand in hand with the community efforts to establish a system. This system should be continually fed to generate positive and steady results by spreading the word, getting recognition and increasing representation and therefore funding. Also, if these efforts aren’t focused on the most marginalized and economically vulnerable population sectors (this could be throughout the development of structures that empower the community such as non-profit soup kitchens, food banks, among others) and on access (availability and distribution of the food by direct markets and stands but also individual purchasing power), urban agriculture will have little impact improving the conditions inside the community.

As authors, we are limited by our own previous knowledge of the movements as we are attempting to seek information we would expect to find on our topics. As students, we are also limited by the timeframe of an assignment such as this, as we attempt to cover an expansive topic quite briefly. The limits of our study are also bound by unrecorded and unpublished local food movements; there may be various movements that have gone unseen which we do not have access too as a group. Finally, our study is bound by the findings within our cited authors’ published work, as their research is constricted by their own limitations, methodologies, accuracy, and source use.

Through our analysis of these two cities’ historical backgrounds and food movements, we were able to answer our research questions of why the movements arose and how successful they have been.

Portland, with a very homogenous urban population, saw their food movement rise out of 1970s environmentalism. The city’s white residents pushed for sustainability as a priority in the city, and their voices were heard loud and clear by policymakers and organizations. The privilege of having a local political body willing to listen and help through policy has allowed the Portland urban food movement a great deal of success, as outlined above. The city is extremely conscious of its’ food production, consumption, and carbon footprint as a result of many decades of successful partnership between food activists and policymakers. The historical lens deepens our understanding of this relationship, as the policymakers of the city have listened to and served its’ white residents for two centuries, sacrificing all other populations to do so. We, therefore, conclude that this movement arose to make the city more sustainable and environmentally conscious through food, and it has been extremely successful.

Detroit’s food movement arose out of a very different political, economic, and social reality. Plagued by vacancy, poverty, political instability, and white flight, Detroit saw it’s food movement rise to answer African American community members questions of food justice and food scarcity. Local organizations have been able to take advantage of strong community ties and vacant lots to form a food justice movement that is now known around the country for its success. However, many of the issues that provoked the urban food movement in Detroit continue to limit its’ growth and success. Funding and political support are huge issues for the movement, as the city still suffers without a strong tax base or political leadership. We, therefore, conclude that the urban food movement in Detroit arose to answer questions of food justice and food scarcity, and while it has been very successful so far, the future is less clear without funding opportunities and political support from the city.

These two case studies shed much light on urban food movements, both in terms of their success and limitations, as well as how those aspects are deeply embedding in the historical realities of place. We believe that every food movement will be unique in its’ objective function as they were serving unique populations in areas with unique histories. However, no matter how strong a movements’ foundations are, there comes an inevitable moment when financial and political realities must be confronted. Fortunately for cities resembling Portland, these are not huge issues as they have the support and ear of the local politicians and organizations. For cities such as Detroit, funding and political support remain big questions in the future.

We believe the next step for movements such as Portlands’ is to become more inclusive. With the strength and support of the city, it’s time this movement includes and listens to the historically marginalized populations in their city. Without doing so, the movement will never be able to serve the entire city of Portland as best as it can. The next step for movements like the one we see in Detroit is to get a food in the political door. These grassroots organizations and movements cannot and could not be possible without strong community leadership, as Detroit has seen in its’ food movement. It’s time for these food justice leaders to go further and look to politics for further strength and funding down the road, whether that be local, state, or national.

Balmer, K. Gill, J, Kaplinger, H, Miller, J, Peterson, M, Rhoads, A, et al. (2005). The diggable city: Making urban agriculture a planning priority. Portland, OR: Portland State University, Nohad A. Touland School of Urban Studies and Planning.

Carney, Patricia A. et al. Cassidy, Patricia A.. "Impact of a community gardening project on vegetable intake, food security and family relationships: a community-based participatory research study." Journal of community health 37.4 (2012): 874-881. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/ article/10.1007/s10900-011-9522-z

Cassidy, Patricia A. Patterson, B. A Planner’s Guide to the Urban Food System; Post Carbon Institute: Portland, OR, USA, 2008. http://www.ca-ilg.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/plannersguide tothefoodsystem.pdf

City of Portland ENN-1.01: Food Policy Council (Binding city policy). Retrieved September 24, 2007. http://www.portlandonline .com/auditor/index.cfm?a=ihci&c=checj

Coggins, J. and Senauer, B. “Grocery Retailing.” pp. 155-178 (Chapter 7) in D. C. Mowery (editor), U.S. Industries in 2000: Studies in Competitive Performance, Board on Science, Technology, and Economic Policy, National Research Council, National Academy Press, Washington, D. C.

Colasanti, K.J.A.; Hamm, M.W.; Litjens, C.M. "The city as an “agricultural powerhouse”? Perspectives on expanding urban agriculture from Detroit, Michigan." 2012. Urban Geogr. 33, 348–369.

Detroit Population 2018 World Population Review. 2018. http://worldpopulationreview.com/us- cities/detroit-population/

Doucet, Brian (editor) “Introduction: Why Detroit Matters.” Why Detroit Matters: Decline, Renewal and Hope in a Divided City, 1st ed., Policy Press at the University of Bristol, Bristol, 2017, pp. 1–30. JSTOR. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1t896c9.6

Draus, Paul J. “We don’t have no neighbourhood’: Advanced marginality and urban agriculture in Detroit.” Urban Studies, vol. 51, no. 12, 2013, pp. 2523–2538., doi:10.1177/0042098013506044.

Duda, M. "Growing in the D: revising current laws to promote a model of sustainable city agriculture." 2012. University of Detroit Mercy Law Review, 89, 181–98.

Eley, Tom. "Census reveals staggering decline of Detroit." World Socialist Website. 20011. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2011/03/detr-m24.html

Finkelman, Paul “The Surprising History of Race and Law in Michigan.” 2006 Michigan Supreme Court Historical Society. Michigan, USA. 27 April 2006. http://www.micourthistory.org/ wp-content/uploads/speeches_vignettes_pdf/the_surprising_history_of_race_and_law_in_michigan.pdf

Fryer, Heather “Race, Industry, and the Aesthetic of a Changing Community in World War II Portland.” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, vol. 96, no. 1, 2004, pp. 3–13. JSTOR, JSTOR. www.jstor.org/stable/40491804

Galster, George “Detroit’s Bankruptcy: Treating the Symptom, Not the Cause.” Why Detroit Matters: Decline, Renewal and Hope in a Divided City, edited by Brian Doucet, 1st ed., Policy Press at the University of Bristol, Bristol, 2017, pp. 33–50. JSTOR. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1t896c9.7

Guptill, A. and Wilkins, J.L. "Buying into the Food System: Trends in Food Retailing in the US and Implications for Local Foods." 2002. Source: Agriculture and Human Values 19: 39-51.

Hendrickson, M. and Heffernan, W. "Consolidation in the Food and Agriculture System." 2007. Source: Washington, DC: Report to the National Farmers Union.

Hortaliza A Youth “Nutrition Garden” in Southwest Detroit Author(s): Kameshwari Pothukuchi Source: Children, Youth and Environments, Vol. 14, No. 2, Collected Papers (2004), pp. 124-155.

Katherine H. and Anne Carter."Urban agriculture and community food security in the United States: Farming from the city center to the urban fringe. Urban Agriculture Committee of the Community Food Security Coalition." (2002). http://ocfoodaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/ 2013/08/Urban-Agriculture-Food-Security_CFSC-2002.pdf

Kaza, G Michigan’s Single-State Recession: When Local Politicians Attempt to Allocate Capital, Local Economies Suffer. National Review Online. 2006. http://www.nationalreview.com/articles/218992/michigans-single-state-recession-greg-kaza

Kurczewski, Nick “This is how Detroit became the Motor City.” Hagerty. 10 Oct. 2016. https://www.hagerty.com/articles-videos/articles/2016/10/10/detroit-primacy

Lovell, Sarah Taylor "Multifunctional urban agriculture for sustainable land use planning in the United States." Sustainability 2.8 (2010): 2499-2522. http://www.mdpi.com/2071- 1050/2/8/2499/htm

Lynn Bartkowiak Sholander Green Thumbs in the City:Incentivizing Urban Agriculture on Unoccupied Detroit Public School District Land, 91 U. Det. Mercy L. Rev. 173 (2014).

McCall, T Legislative address, Governor Tom McCall, Oregon, 1973. Retrieved July 20, 2008. http://arcweb.sos.state.or.us/ governors/McCall/legis1973.html

Mcelderry, Stuart “Building a West Coast Ghetto: African-American Housing in Portland, 1910-1960.” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, vol. 92, no. 3, 2001, pp. 137–148. JSTOR. www.jstor.org/stable/40492659

Mendes, Wendy et al "Using land inventories to plan for urban agriculture: experiences from Portland and Vancouver." Journal of the American Planning Association 74.4 (2008): 435-449. https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/doi/abs/10.1080/01944360802354923

Mogk, J. E., Wiatowski, S. and Weindorf, M. J. "Promoting urban agriculture as an alternative land use for vacant properties in the City of Detroit: benefits, problems and proposals for a regulatory framework for successful land use integration." 2008. The Wayne Law Review, 56, 1–61.

Oregon Blue Book “Oregon History: Emerging Economies.” Oregon Blue Book. 2018. http://www.bluebook. state.or.us/cultural/history/history21.htm

World Population Review “Portland Population 2018” World Population Review. 2018. http://worldpopulationreview.com /us-cities/portland-population/">

Pothukuchi, Kameshwari “Five Decades of Community Food Planning in Detroit.” Journal of Planning Education and Research, vol. 35, no. 4, 2015, pp. 419–434., doi:10.1177/0739456x15586630.

Schukoske, J. E. "Community development through gardening: state and local policies transforming urban space." 2000. Legislation and Public Policy 3: 351-392.

Semuels, Alana “The Racist History of Portland, the Whitest City in America.” The Atlantic Newspaper Online. 22 July 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/ 2016/07/racist-history-portland/492035/

Smith, J.J. and Hurst, N. "Grocery closings hit Detroit hard." 2007. Detroit News. July 5.

University of Virginia. “The Racial Dot Map: One Dot Per Person.” The Racial Dot Map Online. 2010. http://demographics.virginia.edu/DotMap/

Weber, Peter. “The rise and fall of Detroit: a timeline.” The Week Newspaper Online. 19 July 2013. http://theweek.com/articles/461968/rise-fall-detroit-timeline

White, Monica M. “Environmental Reviews & Case Studies: D-Town Farm: African American Resistance to Food Insecurity and the Transformation of Detroit.” Environmental Practice, vol. 13, no. 4, 2011, pp. 406–417., doi:10.1017/s1466046611000408

White, Monica M. “Sisters of the Soil: Urban Gardening as Resistance in Detroit.” Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts, vol. 5, no. 1, 2011, pp. 13–28., doi:10.2979/racethmulglocon.5.1.13.

Wikimedia Commons. “Portland population growth.” Wikimedia Commons. 19 July 2013. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portland_population_growth.png

Zenk, S., Schulz, A., Israel, B., James, S., Bao, S. and Wilson, M. "Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in Metropolitan Detroit." 2005. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 660–67.

This project would not have been possible without the constant discussions and constructive criticism of our Environmental Studies Course, along with guided instruction of Professor Michel A. Wattiaux. We would also like to specifically thank our wonderful TA, Ginny Moore, for not only putting up with us, but for her continued commitment to giving our group constant feedback on the ideas which we have communicated in this study.