Team F: Sustainable Coffee

Note/disclaimer: This webpage is for instructional purposes only and the scenario described below is fictional.

This page was developed as a hypothetical report on the sustainability of coffee written on behalf of students at UW Madison.

Lucy Walker, Major in Biological Systems Engineering with Certificate in Global Health

Megan Landwehr, Major in Agricultural Business Management

Scenario | Abstract | Introduction | Methods | Results | Limitations | Conclusions | Citations | Acknowledgements | About the Authors |

Scenario

Scenario

We are colleagues from the University of Wisconsin-Madison looking to start a sustainable coffee shop. The three most important components we want for our company are sustainability, ethical labor, and of course taste. In order to produce the best product, we conducted research on the different types of coffee production in order to find the best farm that aligns with our values to choose to buy beans from.

We are specifically interested in farms in Uganda, thus our research is centered around intercropping, mono cropping, and plantation techniques in that region.

Why Uganda?Oil is the only commodity that is more widely traded than coffee, making coffee the most valuable agricultural commodity. Coffee is significant in the livelihoods of a large part of the tropical world in developing countries. Uganda depends heavily on foreign exchange from coffee exports, and the economic impact of developments in the coffee market on rural Ugandan communities is potentially large. Because price volatility in international trade has increased over the years, small-scale farmers are hurting because they lack access to larger scale production contracts that offer a fixed price for their coffee beans. We are choosing to study Uganda because of our personal connection and its status as a main coffee producer. Uganda is the second largest coffee producer and biggest exporter in Africa, contributing to the world coffee supply by 2.2%. Lucy has also traveled to Uganda and visited different farms in the southern region of the country, including an intercropping plot of bananas and coffee beans. Seeing first-hand the popularity of small, homeowner crops as a commonality for food and income among many small villagers in Uganda, we are interested to study the different ways coffee is produced in the country in terms of economic, social, and environmental sustainability.

Abstract

Popular coffee companies such as Colectivo Coffee (Wisconsin) and Peet’s Coffee and Tea (California) are finding ways to market a more environmentally conscious product within a sustainable company design while still generating large profits. The root of this business complex is in the coffee itself, the bean. This paper discusses the differences in the benefits of different types of coffee farming, focusing on techniques used in Uganda. Specifically, the intercropping of coffee beans with a tall, shaded crop such as banana plants is discussed in contrast with larger scale plantation style farming in the context of environmental, economic, and social sustainability. We aim to display the cost and benefits of all three pillars of coffee farming techniques in order to find the most sustainable system. For coffee production, there are 3 categories of sustainable farming, organic, fair-trade, and shade grown. A conclusion is made that each technique poses different challenges on production and marketing of the product and exposes the challenges of creating more sustainable solutions in our economy.

Introduction

Uganda is the second largest coffee producer in Africa, yet coffee yields are still poor . The performance of Arabica coffee is strongly influenced by climatic variability and is very sensitive to climate change. To increase farmers' production, a variety of agronomic practices have been recommended by national and international agencies. However, adoption potential of recommendations differs between farm systems. To understand the differences in adoption potential of recommended coffee management practices in Uganda, it is trivial to assess the diversity between the farm types and evaluate the current use of existing management recommendations for each farm type. Research done though factor analysis and cluster analysis of farms producing coffee has identified five farm types in Eastern Africa: large coffee farms, farms with off-farm activities, coffee-dependent farms, diversified farms, and banana coffee farms. The farm types were based on differences in size, and on relative contributions of coffee, banana and off-farm labour to total household income.

For the context of this project, we are focusing on large coffee farms and banana-coffee (intercropping) farms.

In Uganda, most of the coffee is grown in agroforestry systems of intercropping trees and bananas. Ecosystem services from this technique can be economical (e.g. biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration and buggering changes in temperature and precipitation) and environmental (e.g. biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration and buffering changes in temperature and precipitation), and can enhance the sustainability and resilience of agricultural systems.

Many sustainability assessment practices have been developed in recent years, but their transition to practical use for decision making remains a challenge. It has been found that engaging stakeholders is important for implementing sustainable practices and reaching goals.

Additionally, it has been found that small scale coffee growing is a pro-poor intervention.

Many larger scale plantations work to gain Fair Trade USA certification to increase business ventures. Many times, worker rights are what hinder a farm from becoming Fair Trade certified. This creates questioning on the ethics and whether the sustainability of the workplace environment for plantation workers is worth the mass production of beans that plantation farming provides.

Research question: Which sustainable coffee farming technique creates the most sustainable atmosphere in respect to the environment, economics, and quality of life?

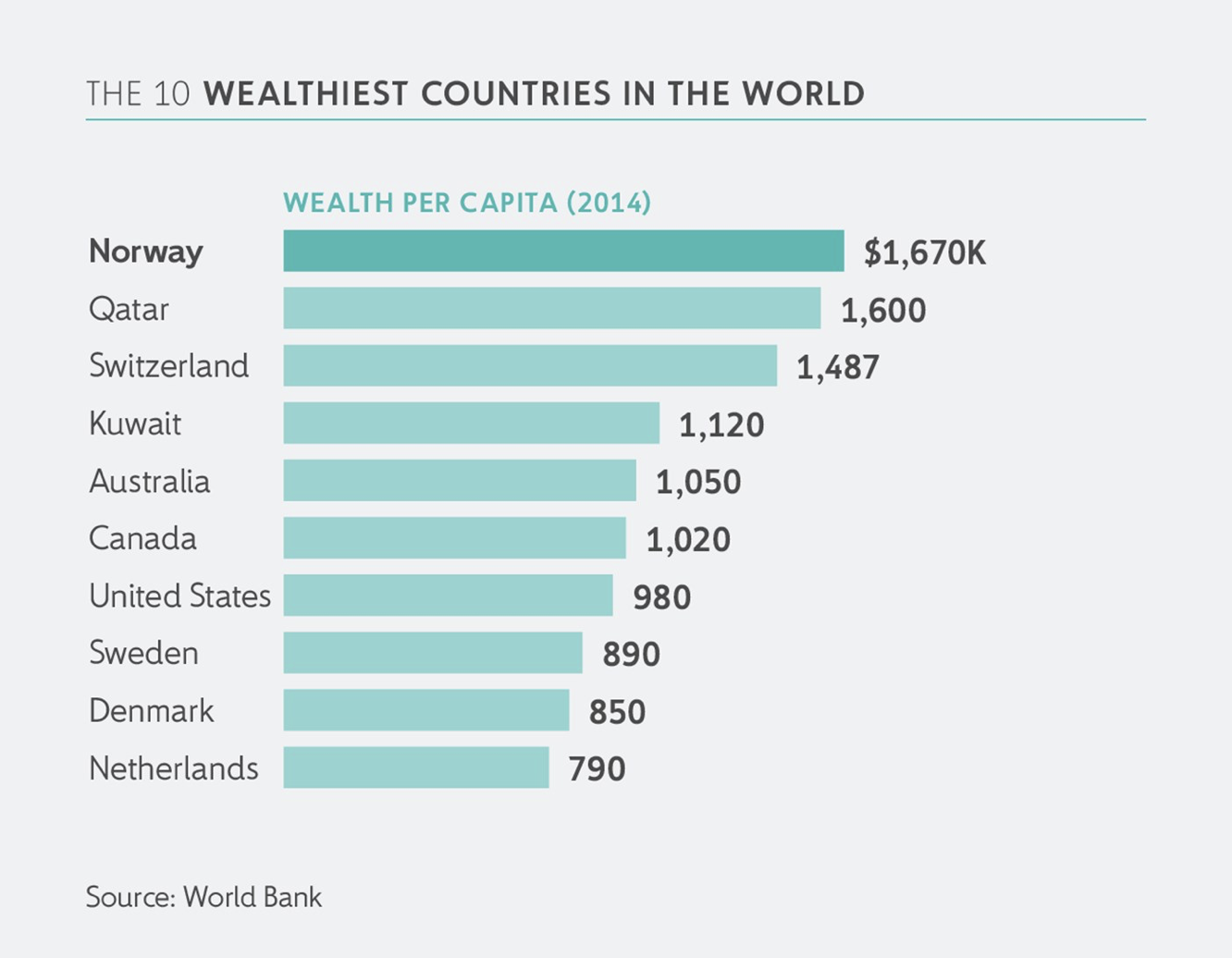

Although some of the world’s poorest countries produce coffee, preponderance of that production is consumed by the citizens of the world’s wealthiest countries.

Coffee is one of the most widely traded global commodities, placing it on the forefront of the debate on how consumer demands can create changes toward sustainable agriculture. Consumers have a legitimate demand for transparent environmental and social impacts, thus sustainable coffee has been gaining significance in high-value markets. Different ways to approach the sustainability of coffee production are from the perspectives of agronomy, biodiversity conservation, as well as economic and social effects. In doing so, opportunities for developing countries to break the continuing cycle of poverty, environmental degradation, and disruption of social stability in local communities, as well as minimizing price volatility. A major problem arises in the link between added consumer value into a tangible income transfer of rural communities in the international coffee market that is dominated by large-scale roasters.

If the structure of the marketing chain is strong, coffee certified according to sustainability standards commands a premium price that can put more money in the hands of the producers. The marketing aspect is a promising and successful way to harness consumer willingness to pay for environmental and social values that sustainable coffee production encompasses. The key to market success for sustainable coffee is a functioning supply chain and a credible certification method. The three major certification schemes are organic, fair trade, and shade grown. They differ in characteristics but tend to converge in terms of social criteria in organic certification regulations.

The current market for sustainable coffee is small, but it is growing rapidly. The price premium paid to producers of certified sustainable coffee can be a major source of additional income. Organic and shade-grown coffee are traded at premiums over the price paid for conventionally grown coffee. The fair-trade label offers a guaranteed floor price when world market prices are low. This long-term security of direct marketing link, encouraged through the certifying sustainable coffee, can be extremely important for a potentially large amount of the rural population.

Since the demand for sustainably grown coffee is apparent and we can use the marketing to sell at a higher price point, it is the direction our coffee shop desires to go. The research, however, needs to direct what private certifications, if any, produce the most sustainably grown coffee beans in Uganda. It is important that the beans produced are produced in an environmentally sustainable environment with that is socially and economically sustainable for the producers. Through this research, the intention is to identify what private certification, or combination of certifications, provide the best sustainability to Ugandan coffee growers.

Hypothesis

Methods

To gather information about the different techniques for farming coffee, we reviewed a variety of peer reviewed journals, scientific articles, and interviewed a specialist. By formulating a subset of research questions, we focused on the definition of sustainability in terms of environmental impact and treatment of laborers on the farm. The research done varies dramatically depending on which of the pillars of sustainability is under question. For example, research into the economic sustainability of intercropping comes from observing trends in the coffee trading markets in order to understand the price fluctuations on both the yearly cyclical trends, as well as the overall price trend. These observations are then compared with the “farm gate” prices that are provided as data from coffee cooperatives in Eastern Africa and the rest of the world. The data that underlies the assumptions of this research, however, is limited due to confidentiality as price information is an important part of private sector trade.

Bias Prevention

Unlike the easily measurable metrics for economic sustainability, which is measured in dollars, social and environmental sustainability can be measured on a variety of metrics, each with their own biases and spin on the data. Research into the social pillar comes from previous studies that answered measured labor usage in monocropping and intercropping coffee farms in Eastern Africa. In order to gain a wider view of the intercropping versus monocropping debate, data from Nicaragua was also considered (Raynolds, 2019). Viewing this Nicaragua data has ensured a balance in what is observed in Eastern Africa, essentially providing additional data that roughly translates from continent to continent.

Research into environmental sustainability considers many different aspects including water consumption, climate change, nutrient usage, and erosion. Since each of these is measured using a different metric and not easily comparable, intercropping and monocropping will be compared on each individual topic and then the results will be tallied. For example, if intercropping is deemed the better option from the perspectives of climate change, erosion, and water consumption but mono cropping is preferred from a nutrient usage perspective, intercropping will be deemed more environmentally sustainable for the purpose of this research.

Discussion & Results:

While initially we included taste into one of the main considerations for our operation, research shows that it is less important than other factors, such as the branding of eco-friendly coffee and our focus on being a study spot on the college campus. Research was done by Patrik Sörqvist on the perception of taste of coffee after believing that one was ‘eco-friendly’ and the other was not; this research found that when the two coffees being tested were the same, the participants found the ‘eco-friendly’ to taste better. While this research is not going to be used in the context that quality is not important, it is important to remember that taste is less important when the coffee can be branded as environmentally friendly.

Different Sustainability StandardsThree different method are discussed throughout this paper: organic, shade-grown, and fair-trade. Organic Coffee is centered on agronomic practices. Beans are grown without the use of synthetic chemical fertilizers and pesticides through sustainable agricultural methods. Shade trees are important for organic production because lead litter fertilizes the production, and the trees retain moisture and provide a habitat for the natural enemies of coffee pests. Shade-grown coffee is grown under a canopy of shade trees that provide a habitat for migratory birds and other species, enrich and conserve soil and decrease the need for chemical inputs. Fair trade coffee provides an alternative trade model. Certified fair-trade coffee is exchanged at a guaranteed minimum price, which can be almost twice that for conventional coffee. Rules encourage healthy working conditions and a living wage for farmers, as well as financing of community-level development activities by farmer organizations.

Social Sustainability

There is no aspect of sustainability that is more important than the other, but from a marketing perspective, social sustainability appears to be a large factor. The region we selected, Eastern Africa, was chosen in part because it has the biggest opportunity for social impact.

As it currently stands in Eastern Africa, there is little government oversight that protects the farmers growing the crops, which allows for wide reaching social injustices. Much of this injustice surrounds the struggle to keep coffee growing economically sustainable for the farmers themselves. While the economic sustainability of intercropping is discussed in a later section, it is important to note that from a labor standpoint, intercropping is much more sustainable than mono-cropping. This sustainability comes from the opposite cycles that coffee and banana plants require. Throughout the year, both coffee and bananas require labor in the form of general upkeep as well as harvesting, however the yearly cycle of each plant comes at separate times, so they are not requiring labor at the same points. Because these plants have complementary cycles, there is not an excess demand for labor at one period and no demand at another, this is especially important for larger farms who hire labor as it allows them to provide jobs year-round.

Economic Sustainability

At the start of a coffee farm’s life, intercropping can be very beneficial as it provides a secondary source of income as the coffee plants mature, which takes several years. For the first several years, the secondary crop in the intercropping system acts as a primary source of food and income. In Eastern Africa, this is normally bananas, which are an excellent source of nutrients for farmers. Any bananas not consumed by the farmer or their family are then sold and act as a revenue generating operation.

Once the coffee plants are mature enough to produce beans, they become the primary income source in the intercropping situation, with the bananas taking a secondary role. Intercropping still, however proves to be more economically viable than monocropping due to harvesting patterns. Because bananas and coffee are harvested at separate times, the farmers who intercrop have a steadier flow of income throughout the year, as opposed to one large source of income per year from just the coffee. Having another revenue producing crop also allows farmers to reduce risk from environmental factors such as drought or pests which may cause extensive damage to coffee plants.

From a quality side, during the beginning years of intercropping, the beans produced are of a higher quality, an important aspect to a coffee shop focused on a quality product. This also allows coffee farmers to sell their beans at a higher rate. From a sustainability side however, this is not long lasting for as the coffee plants continue to mature, they start competing for nutrients in the soil as bananas and coffee beans both require similar nutrients to be produced. With the competition for nutrients comes smaller yields of both bananas and coffee beans, which in turn results in a smaller harvest revenue for the farmer.

The coffee industry is far from steady, with prices constantly fluctuating in extreme swings, it is very difficult for farmers to predict what their harvest revenues are going to be for the season. More recently, prices have fallen dramatically, with prices dropping to a third of what they previously were over a four-year period at the turn of the century. These dramatic price decreases showed the value of intercropping, as the secondary crops were suddenly what was keeping these small coffee farms afloat. For the farmers, intercropping all or most of their fields makes the most economic sense in the long run because it allows them to reduce risk by diversification.

As the system currently stands, coffee growers in Eastern Africa ship their green coffee beans to Europe to be roasted, and then from there they are sold to distributors. This is also the greatest area of opportunity for Eastern Africa to increase the profits of their coffee growing operations and provide stability for themselves as a region of coffee growers. The economic stability in this comes from the relatively consistent price for roasted coffee beans as a final product.

From our perspective as a consumer of roasted coffee beans, sourcing our product from Eastern African coffee roasters would allow us to purchase the roasted coffee beans at a price consistent, or even slightly less than the European roasted beans, while providing greater revenue opportunities to the rural coffee growers in Eastern Africa.

Environmental Sustainability

Intercropping coffee and bananas is the least sustainable from the perspective of environmental sustainability. While beneficial in the beginning for economic reasons, and providing some social benefits as well, as time goes on the environmental impacts of intercropping continue to decrease. The decrease is due to the competition of the coffee and banana for the nutrients needed to produce their fruit and beans.

This is not to say that there are no environmental benefits to intercropping. In fact, the environmental benefits of intercropping are strongest amid natural disasters, much like the economic ones. Due to the roots of the banana plants, during natural disasters such as strong winds and rains, the roots help keep the soil intact and compete against erosion. By keeping the soil where it needs to be, the banana plants help keep farms from experiencing the devastation that natural disasters can bring.

Water usage is not a clear indicator of which growing method is more sustainable either. The amount of water required for crop coffee is the 5th highest in Uganda compared to other coffee producing countries as examined with a virtual water content of 17079 meters cubed per a ton of green coffee. The water requirement of coffee differs slightly depending on the climate, and hence on soil conditions and rainfall patterns. It also depends on whether the coffee is wet or dry processed. Wet processed coffee adds more economic value to the bean as the process requires more resources.

A case study conducting in Uganda found the demand for washed Arabica, which is used for coffee production, has increased in global demand over the past years. Farmers are now influenced to wet process their coffee beans as it will guarantee higher price for their products. However, farmers are limited in terms of inputs adapting to this new market opportunity. Uganda is considered a water abundant country. Coffee farmers rely heavily on rainwater and river water to cover all primary water consumption. However, Uganda has a rainy season and dry season, and climate change mixed with the surge in demand for washed Arabica has not mixed well. A more reliable water management is desirable in the coming years to enhance the livelihood of smallholder coffee farmers

Climate change also cannot point to a clear choice for a more environmentally sustainable option as well, but it certainly influences the coffee market. As is the case for many agricultural commodities, coffee plants are prone to increasingly unpredictable weather conditions associated with global climate change. Droughts mixed with erratic rainfall have detrimental effects on flowering and the cherry maturation. Drought by itself can cause a production loss up to 20% while unpredictable rainfalls deteriorates the quality of beans. Excessive rains can lead to the spread of diseases such as the Coffee Wilt Disease, which killed an estimate of 200 million trees in the past 10 years in Uganda.

Limitations

Limits of ecosystem services on coffee productivity include local environment, livelihood strategies of producers, local market conditions, and management practices.

Limits of stakeholder needs and values. The priority at which stakeholders place sustainable goals for their farms depends highly on the type of stakeholder and how engaged they were during the learning process.

The Fair Trade model has changed little since its inception. While the price and premium for coffee has been adjusted upward over time, the regulations for achieving fair trade status have barely been revised. Their chief goal being consumer awareness, new solutions for integrating sustainability and transparency are needing to be built into the supply chain to mend the bridge between added consumer value into a tangible income transfer of rural communities in the international coffee market that is dominated by large-scale roasters

Conclusions

Comparisons About Sustainability: The agroforestry system of intercropping coffee trees and other food crops such as bananas and sometimes maize supports the long-term sustainability of coffee yields and conserves water, soil, and biodiversity. The ‘intensification’ of traditional shade coffee systems into ‘sun coffee’ plantations has major environmental implications. While coffee plantations have higher yields in the short run, given the use of external inputs and higher tree density, it raises many concerns about the long-term sustainability of the production gains. The conversion from shade coffee to sun coffee leads to clear cutting of tropical forest trees, higher soil erosion, and higher run-off of agrochemicals.

Aiding the Transition to more Sustainable Coffee: The transition to more sustainable coffee offers opportunities for a market-based solution to reduce rural poverty and conserve biodiversity in many developing countries, making it admirable for policy-makers support. To contrast rural development activities of the past, promotion of sustainable coffee for differentiated markets should first pay attention to securing access to high-value markets with high-quality coffee. This idea is critical if producers are to reap the rewards from the environmental and social services that their production method is providing as it is key to successful long-term contracts with coffee buyers, such as our coffee company.

A major challenge in this transition to sustainably grown coffee is the producers’ ability to cope with the requirements of certification, monitoring, and documentation. Certification costs are a large investment, especially for countries that must rely on certification from foreign bodies before being able to enter export markets. Development projects can assist small-scale producers by offering technical assistance and cost sharing. Finally, consumer awareness is a large aspect in the transition to sustainable coffee production.

Domestic agricultural policies are frequently geared toward supporting “technology” based coffee, meaning through input and credit schemes, subsidies and tax breaks for agrochemicals, research priorities, and extension organizations. Producer groups often need to increase their technical and institutional capacity to meet the quality demands of the market. Through policy changes and promoting of the local and global benefits of sustainable coffee for rural development and their environmental protection, it is hopeful that corporate biases can be reversed.

When putting everything together, the choice for shade grown, fair trade coffee has become the clear choice. Having shade grown coffee is better for the environment in the long run and preserves the integrity of the soil for future farming generations. Having the price floor that fair trade certification offers is the most efficient way to make sure that farmers are protected from the volatile market. While the dual certification may be more difficult to get, it’s important to make sure that the coffee sold in this coffee shop is the most sustainable it can be. The next progress that is required is to either find a farm that already meets these standards, or to work on a development plan alongside policy makers to influence and take an existing farm and help them to receive and maintain the certifications.

Citations

Akoy, K. &. (n.d.). Walk the Talk: Private Sustainability Standards in the Ugandan Coffee Sector. . Journal of Development Studies, 1792-1818.

Bacon, C. F. (2008). Cultivating Sustainable Coffee: Persistant Paradoxes. Confronting the Coffee Crisis, 337-372.

Beckerman, S. (n.d.). Toward More Sustainable Coffee.Rural Development Department of The World Bank.

Chapagain, A. K. (2007). The water footprint of coffee and tea consumption in the Netherlands. Retreived from Enschede: University of Twente. .

Gram, G. e. (2017). Local Tree Knowledge Can Fast Track Agroforestry Recommendations for Coffee Smallholders along a Climate Gradiaent in Mount Elgon, Uganda.

Jassonge, L. v. (2013). Perceptions and outlook on intercropping Coffee with banana as an opportunity for smallholder cofee famers in Uganda. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 144-158.

Mbowa, S. e. (2017). Does Coffee Production Reduce Poverty? Evidence from Uganda.

Meylan, L. e. (2017). Evaluating the Effect of Shade Trees on Provisions of Ecosystem Services in Intensively Managed Coffee Plantations.

Nderitu, T. (2010). Kenya: Bitter Brew: Kenya's Women Coffee Farmers Face Rough Times. Women's Feature Service.

Raynolds, L. R. (2019). Fair Trade USA Coffee Plantation Certification: Ramifications for Workers in Nicaragua.

Sherfey, J. (2016). The 10 Most Sustainable Coffee Businesses in the United States

Sörqvist, P. (2013). Who needs cream and sugar when there is eco-labeling? Taste and willingness to pay for “eco-friendly” coffee.Plos.

Ssebunya, B. R. (2016). Stakeholder Engagement in Prioritizing Sustainability Assessment Themes for Smallholder Coffee Production in Uganda.

Tumwebaze, S. B. (2016). Soil Organic Carbon Stocks Under Coffee Agroforestry Systems and Coffee Monoculture in Uganda.

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been successful without the contributions of the outstanding students in our Food Systems, Sustainability, and Climate Change class as well as our professor, Dr. Wattiaux and T.As MaryGrace and Brittany for all their assistance and help finding articles. We would particularly like to acknowledge the wonderful and challenging questions, and the specific knowledge that students with different areas of expertise provided.

About the Authors

Lucy Walker is a junior in the Biological Systems Engineering and Global Health programs at UW-Madison. Raised in Seattle, Washington she grew up with a coffee shop on every block, including a Starbucks on her high schools campus! This exposure to coffee culture sparked her passion towards sustainable solutions to coffee growing. She is interested in creating sustainable farming techniques that reduce industrial agriculture's impact on climate change and promote human health.

Megan Landwehr is a senior in the Agricultural Business Management program at UW-Madison. Growing up in an agriculture background, she's passionate about educating everyone on the impact that farming has on our communities and helping create a sustainable agricultural system for the future.

.jpg)